My application recently finished switching from a master-slave database configuration to Apache Cassandra (version 2.0.4). This took my team around four months, involved rewriting every part of our application that touched the database, and migrating all existing data (we managed to do this all without downtime!).

mysql dead. hail cassandra

— Dave (@tildedave) February 21, 2014The availability guarantees provided by Cassandra were the main motivation for this switch: the database has no single point of failure. The week after we finished our switch, I had to fill out a business continuity plan: our application failure scenario went from the loss of a single node (our MySQL master) to the simultaneous unrecoverable loss of three complete datacenters. Combined with a Global Traffic Manager setup across our three datacenters, Cassandra will allow our site to remain operational even if two of them fail, all without the loss of customer data.

Of course, even though the database has no single point of failure, that doesn’t mean that your application stays up. It’s no good having a highly available database if you only have one edge device handling all incoming traffic. During our database migration, we ran into a number of application-level failure scenarios – some of these we induced ourselves through our test scenarios, while others happened to us in our lower environments (staging, preprod, test) during the slow march to production. Each of these failures was not due to a failure of the database, but the failure of components that we added on top of it.

In this article, I’ll go over some of the different failure scenarios we ran into, along with how we solved them (or in some situations, plan to solve them). Much of the work described here was done by my team and not by me personally. Though I eventually got into writing some of the code, I served mainly as an engineering manager on this project – while I found some of these issues, handling the resolutions was mainly done by others on the team.

Querying Cassandra with the Datastax Python Cassandra Driver

The parts of our application that talk to the database are written in Python: we have application servers written in both Django and Twisted – however, given that we don’t use SQL any more, the project has been quickly shedding its ‘Djangoisms’.

There are a number of Python Cassandra drivers out there; however many (for example, pycassa) didn’t support CQL3, a SQL-like language for querying Apache Cassandra that was introduced in the Cassandra 1.2 release. From reading around online, CQL3 was clearly the “new way” for code to query Cassandra (as opposed to using Thrift directly). The Datastax Python cassandra-driver was an exciting new project with CQL3 support which handled a number of failure scenarios “out of the box”. Though when we started the driver was beta software (it has since had a 1.0.0 release, which we are using in production today), we determined that it was the best choice for Cassandra integration.

There are some Getting Started docs and one of our team members wrote a guide for setting up SSL. The basic concept is that a thread creates a Session object which handles the communication with Cassandra by sending queries and returning results back.

from cassandra import ConsistencyLevel

from cassandra.cluster import Cluster

from cassandra.policies import DCAwareRoundRobinPolicy

from cassandra.query import SimpleStatement

CASSANDRA = {

'NAME': 'mykeyspace',

'HOSTS': ['192.168.3.4', '192.168.3.5', '192.168.3.2', ],

'DATACENTER': 'ORD',

'PORT': 9042

}

c = Cluster(contact_points=CASSANDRA['HOSTS'],

port=CASSANDRA['PORT'],

load_balancing_policy=DCAwareRoundRobinPolicy(local_dc=CASSANDRA['DATACENTER']))

session = c.connect(keyspace=CASSANDRA['NAME'])

rows = session.execute('SELECT name FROM users WHERE username="davehking"')

# Statements are better when you need to pass values in

address_query = SimpleStatement('SELECT address FROM users where username=%(username)s',

consistency_level=ConsistencyLevel.LOCAL_QUORUM)

rows = session.execute(address_query,

parameters={ 'username': 'davehking' })

# Prepared Statements are even better when you execute a query a lot

prepared_address_query = session.prepare('SELECT address FROM users where username=%(username)s')

prepared_address_query.consistency_level=ConsistencyLevel.LOCAL_QUORUM

rows = session.execute(address_query,

parameters={ 'username': 'davehking' })

Our Cassandra Toplogy

We run 15 Cassandra nodes in production: 5 per datacenter, 3 datacenters, with 3 replicas of all data per datacenter. We use the NetworkTopologyStrategy and have the Cassandra nodes gossip over their public network interfaces (secured with SSL).

# cassandra-topology.properties

# DFW CASSANDRA NODES:

106.82.141.183 =DFW:RAC1

89.192.56.21 =DFW:RAC1

73.138.104.236 =DFW:RAC1

134.10.31.175 =DFW:RAC1

134.84.228.145 =DFW:RAC1

# ORD CASSANDRA NODES:

63.241.224.74 =ORD:RAC1

74.254.172.14 =ORD:RAC1

43.157.11.149 =ORD:RAC1

238.152.78.73 =ORD:RAC1

89.133.93.162 =ORD:RAC1

# SYD CASSANDRA NODES:

17.196.144.150 =SYD:RAC1

206.174.71.86 =SYD:RAC1

3.44.230.66 =SYD:RAC1

31.199.140.105 =SYD:RAC1

199.57.119.242 =SYD:RAC1

# cassandra.yaml

# The address to bind the Thrift RPC service and native transport

# server -- clients connect here.

#

rpc_address: 192.168.4.8

# Address to bind to and tell other Cassandra nodes to connect to. You

# _must_ change this if you want multiple nodes to be able to

# communicate!

#

listen_address: 43.157.11.149

We use Rackspace Cloud Networks for querying Cassandra intra-DC a datacenter. While a Cassandra node is gossiping on its public interface 17.196.144.150 (listen_address in cassandra.yaml), it will be receiving queries on its private interface 192.168.4.3 (rpc_address in cassandra.yaml). Inside a datacenter, it’s superior to use private networks to the Rackspace-provided ServiceNet for both security and speed purposes.

Application Failure Scenarios

With the context around our setup (both from an application and cluster perspective) clear, I’ll now describe the issues that we ran into. Though I consider our setup fairly standard (NetworkTopologyStrategy, mod_wsgi for Python execution), we ran into several deep issues that were a natural result of these choices.

Cassandra Doesn’t Care If Your rpc_address is Down

This difference in rpc_address and listen_address became a problem, as these interfaces could fail separately. During our testing, we ran into situations (though infrequent) where Cloud Servers couldn’t communicate over their private interface but were still able to communicate over their public interface. In this case, the Cassandra nodes were still receiving gossip events over their public interface (listen_address) and so were not marked as down – however, the nodes were unqueryable over their private interface (rpc_address).

The current version of the Datastax python-datastax properly handles what happens when a Cassandra node is down on its listen_address: the Cassandra Cluster sends a STATUS_CHANGE message that the host is down and the driver updates its list of ‘good’ hosts, removing its rpc_address from the list of queryable nodes. However, in the event that rpc_address becomes unusable, no STATUS_CHANGE message is sent, and queries on that Session will fail with an error from Cassandra: OperationTimedOut.

Our workaround here was to re-establish a session on this timeout exception being thrown and retry the query. The newly created session will identify that the partially failed node is unreachable, meaning it is not included as a candidate host to query, and subsequent queries will succeed.

Customer-Controlled Tombstones Became a Denial-of-Service

The first table we converted from MySQL was one that handled ‘locking out’ an account after too many failed logins. Our MySQL solution was a fairly straightforward relational solution: on a failed attempt, insert a record into a database. On a login attempt, query the database to determine the number of failed rows – if the number exceeded a specific threshold, the login would be denied. This login attempt would be recorded as a failed attempt along and inserted into the database.

A direct translation of this into Cassandra, with a TTL to auto-expire failed login attempts after a ‘cooling down period’, ran into an issue where a single customer (me, using ab, in our test environment) was able to effect a denial of service for all logins through creating a large amount of garbage records. Once the records for these failed logins had expired, all queries to this table started timing out. The Cassandra logs pointed us to exactly why:

WARN [ReadStage:99] 2013-12-06 19:42:52,406 SliceQueryFilter.java (line 209) Read 10001 live and 99693 tombstoned cells (see tombstone_warn_threshold)

ERROR [ReadStage:155] 2013-12-06 20:04:49,876 SliceQueryFilter.java (line 200) Scanned over 100000 tombstones; query aborted (see tombstone_fail_threshold)

By converting our relational table directly into a Cassandra column family, we inadvertantly introduced a Cassandra anti-pattern, which broke all logins through with a TombstoneOverwhelmingException. As a result of this, we rewrote our login throttling logic to not generate a row per failed login. I think this points to a general principle for column family design: if you’re dealing with TTLed data, different customer actions should not generate different rows.

Partial Failures are Worse Than Total Failures

In contrast to bad column family design (something we honestly expected to fail at given our newness with the technology), the last set of issues we ran into were due to improper management of the Session object that handles the connection to Cassandra.

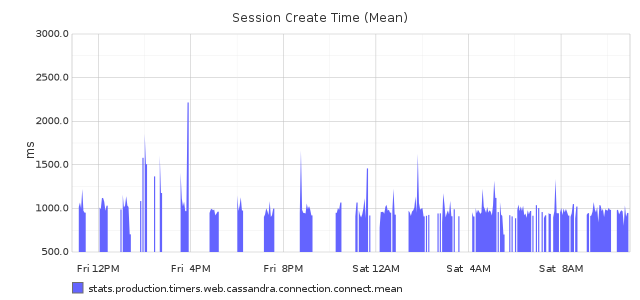

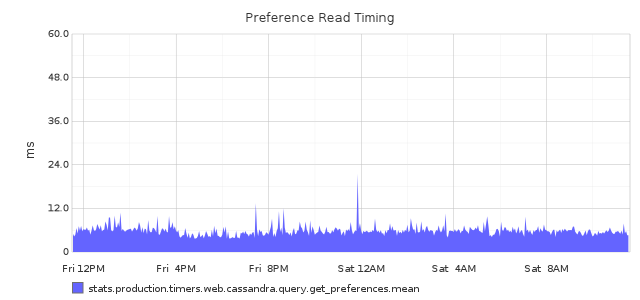

Creating a Session object requires the application node to communicate with the Cassandra cluster to determine which nodes are up and which are down. On average creating this session took 1 second; sometimes spiking up to 4 seconds; in contrast, once a session has been created, our most common database queries finish in less than 10ms. That’s a difference factor of 100.

Because of this time disparity, the reuse of the Session between different requests is key to a performant application. Our Django servers run on Apache through mod_wsgi: each WSGI process reuses one Cassandra Session. We use the maximum-requests setting which eventually kills each WSGI process after a certain number of threads, creating a new one. This new process creates its own Session object and uses it for its lifetime. (In contrast, our Twisted servers are single-threaded and create one Session that is used throughout the lifetime of the process – generally, until it is restarted as part of our code deploy process).

Just as our Cassandra nodes sometimes lost private network connectivity (bringing down the rpc_address while keeing the listen_address up), our application nodes also sometimes experienced failures in private network connectivity. In this case, every host in a mod_wsgi process’s Session object would become marked down, eventually terminating the event loop for the control connection. This meant that every subsequent query with this Session would fail with a NoHostAvailable exception; the Session object will never recover and needs to be recreated.

Making this failure scenario worse is that for our Django application servers, this is only a partial failure of the service. Some WSGI processes are healthy, meaning that they can query Cassandra and get results (notably, loadbalancer health checks will still sometimes succeed), while others are sick, throwing Internal Server errors on every attempt to query the database. Though we use mod_wsgi with Apache, this failure scenario applies for any other approach where different processes respond to requests on the same network interface.

When our Twisted servers have suffered private network failure their health checks have completely failed, since there is only one thread of operation and so only one Session object created. With a failing health check, the service is taken out of rotation in the load balancer. It’s inconvenient that we have to manually restart them (though we could certainly automate that); however, they aren’t serving any errors. I prefer this total failure without customer impact to a half-failure where application servers continue to serve 500s.

We haven’t found the best solution for this issue yet. We’re thinking of investigating history-aware health checks to get a better sense of whether or not a whole service is “sick”. My preferred solution, rewriting our Django servers in single-threaded Twisted Web is probably too much work to justify the result.

My Take-Aways

Redesign your relational tables when moving to Cassandra – ideally, aim for a single row per concept.

Our initial failure in access control table design is a great example of how tables need to be fundamentally redesigned when moved from a relational to a non-relational structure.

Networking failures that do not affect gossip will not be detected by Cassandra, these are your application’s job.

Because our Cassandra nodes gossip only on PublicNet, it will not detect Private Network failures. This leaves it to the application to recover from this failure scenario. It might be possible to alleviate this by setting up the Cassandra cluster to accept queries on PublicNet over SSL and having the application servers only use this address in a fallback case (e.g. defining our own query policy similar to the DCAwareRoundRobinPolicy). We may also investigate whether expanding the Cassandra cluster to use the dc_local_address in a YAML Network Topology Strategy file rather than the default NetworkTopologyStrategy property file would similarly cause gossip to fail in a private network failure scenario.

If you have any differing state between requests, health checks are lies.

If there is any shared state between different requests to the same thread in a process-based web server (such as mod_wsgi), there is a potential for health checks to be inaccurate, meaning that unhealthy services are not be properly marked as down. Ideally individual WSGI processes would be health-checkable, or threads that were unhealthy would somehow kill themselves. In contrast, with a single-threaded web server, application state will be consistent between every request, making health checks actually meaningful.

Though I’ve talked here about the failures we’ve run into, we’ve had a great time with Cassandra in general – there’s been great help available in the community and from the #datastax-drivers team in FreeNode in particular. When I left academics four years ago there was a lot of buzz around Cassandra as an exciting new technology; however, with its reliance on Thrift for querying, it seemed best-suited to stick to Java applications. With the introduction of CQL3 and a drivers for general-purpose languages, it is a great tool for building high-availabilty applications across different datacenters.