My team, the Rackspace Cloud Control Panel, practices continus delivery; our practices are that once code is merged into the master branch, it should be in production within two hours. (I wrote before about how we did over ten production releases on our launch day.) The speed at which code can make it to production and address customer needs is a great thing: however, without an involved manual testing phase there are a lot more opportunities for defects to escape.

Our main strategy for preventing defects is acceptance testing. We use a combination of Selenium Webdriver, Firefox, and RSpec to ensure that we haven’t introduced any problems before we deploy to production. After code is been merged and passed unit tests, it is deployed to a preproduction environment where more than 20 test suites run to verify that everything still works. Each of these suites finishes in less than ten minutes. Work that comes out of the gate comes with ‘acceptance tests included’: a story is not completed until its acceptance tests are automated and passing consistently.

The net effect that these tests have had on the product has been extremely positive and we deploy to production with confidence. The success of our pipeline has been a team effort, involving a lot of work from people with a variety of different job titles (it has not simply been the job of ‘quality engineers’). Throughout all of this, I’ve been learning along with the rest of the team.

The main take-away I’ve gotten from our acceptance test suite is that if something is not tested at the acceptance level and consistently kept green, it will break. The converse of this is also true: if the acceptance tests accurately describe how customers use the system, releases can be done very frequently without any danger at all.

What Are We Automating?

The main chunk of our automation focuses on happy-path automation of user actions. For example, we verify that you can create a server through the WebUI. We add assertions corresponding to the user story: for example, after server creation, the initial root password is properly displayed in the UI.

The main different between acceptance tests and unit tests the level of visibility that they expose of your system. Unit tests are technically facing and describe the individual objects within the system. Acceptance tests are user facing and describe what the customer sees.

I’ve written unit tests that have engaged deeply with the event hierarchy of an object: trigger an event, ensure that object updates itself correctly – update the object, ensure that the correct event gets fired. This is appropriate behavior for a unit test, but writing these tests at the acceptance level breaks abstractions and can cause brittle tests.

Assertions in acceptance tests need to be guided by what the customer sees. For example, if it’s really important that a customer sees the root password after creating a server, an assertion needs to be added for it.

Here’s an example of what one of our tests looks like:

describe('create DNS record') do

let(:setup) { DataSetup::DnsSetup.new @selenium_driver}

let(:list_view) { PageObjects::DnsListView.new(@selenium_driver) }

let(:details_view) { PageObjects::DnsDetailsView.new(@selenium_driver) }

before(:all) do

@domain = setup.create_domain

end

after(:all) do

setup.delete_domains [@domain[:domain_name]]

end

it('creates an A/AAAA type record from details view') do

hostname = RandomData.alphanum(8)

ip_address = RandomData.ipv4_address

details_view.go_to(@domain[:domain_name])

details_view.add_record({

hostname: hostname,

type: 'A/AAAA',

ip_address: ip_address

})

details_view.records_list.join(',').should include(hostname)

end

end

Most interaction with the page is done through page objects, which abstract the details of how the page is represented in the DOM away: details_view.records_list returns a list of displayed records in the table, but the test doesn’t have any selector or interact with the @selenium webdriver object at all. Additionally, the test is structured just like any Arrange-Act-Assert unit test: it sets up its own data (the domain the record is being added to) at the start and destroys it at the end.

Currently the level of assertion is determined by the development team (including both quality engineers and software developers). We don’t involve our product team in defining what assertions are necessary, though this practice is followed by other teams across the industry and tools such as Fitnesse exist to support this.

Tests Must Pass Consistently

It’s no good to write an acceptance test and have it fail frequently. If enough of your tests are unstable, you won’t trust the tests. Because you aren’t trusting the tests, you get no feedback when they fail and it’s very possible for defects to get introduced that the tests would have caught.

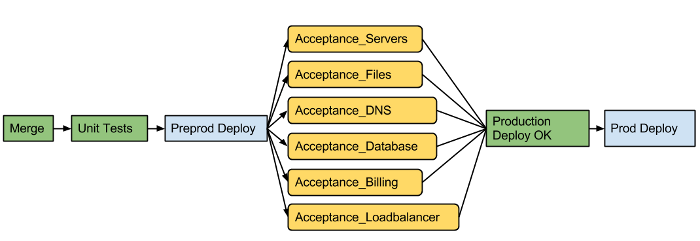

The way we enforce this on our team is that once code is merged, a set of known ‘good’ test suites run (we have 20+ of these now), and after they all pass, a Jenkins job “Production_Deploy_OK” runs, which contains the artifacts distributed by our deployment engine during a production deploy.

Ideally every test runs and passes every time. In practice this isn’t always the case for a lot of reasons that I’ll get into further down. If a test fails, manual intervention is required: team members can override a failure by manually forcing a Jenkins job “Production_Deploy_OK”. Generally if any test fails, it is rerun. While we have usually have more manual overrides than automatic runs of our “Production_Deploy_OK” jobs, all test suites run in under 10 minutes, making reruns generally not too onerous.

By forcing manual intervention we ensure that the default state of these tests are passing, and if a suite starts to behave poorly we will remove it from the set of ‘blocking’ tests and create a defect to investigate and fix it.

Focusing on the Root Cause of a Failure

Acceptance testing in a heavily service-oriented application comes with a number of unique challenges. The main difficulty is in correctly identifying the root cause of a failure. As an example of why this is hard we have had issues involving:

- data setup and teardown

- bugs in our application with varying incidences of reproducibility

- bugs in other services with varying incidences of reproducibility

- behaviors that are different between ‘staging’ and ‘production’ service versions

- tests taking too long because of test behavior

- tests taking too long because of other services

- bugs in Rackspace SDKs (that we use to aid the tests)

- new service versions that have broken Rackspace SDKs

- selenium race conditions caused by poorly written tests

- selenium race conditions, caused by nondeterministic/as-yet-unexplained phenomenon

With a lot of reasons that a test might fail, be sure that you are fixing the actual root cause! Otherwise you are either compromising your level of testing or glossing over real problems.

As simple as it might seem, the scientific method is a great way to identify root causes when a lot of different factors are possibly at play; form a hypothesis based on what you know, conduct an experiment, and see if the results validate your hypothesis.

If a backend service is believed to be at fault (hypothesis), an experiment might test its behavior directly through a service’s SDK (or even curl from the command line if you are interacting with a RESTful service).

If the UI is believed to be the cause of a problem (hypothesis), an experiment might run automation on one particular user-interaction style (e.g. a dialog) a thousand times. Our larger test suites will sometimes run 30-40 tests, of which only 3-4 might exhibit bad behavior. By running only the troublesome tests, you can get a better idea about what might be the problem, rather than wait for the rest of the suite to do its job, which is just wasted time.

Because web applications involve a number of different technology stacks, it’s really easy to get pulled out of your comfort zone when investigating an issue. I’ve found that it’s good to involve other people on the team early and work together to validate your assumptions. A different perspective might also suggest possibilities that you may not have considered.

Conclusion

Before my current project I was a firm believer in unit tests and didn’t quite understand the focus on end-to-end system tests (this despite the fact that my first paid software job involved creating test harnesses for integration-level suites). In helping to build our pipeline, I’ve come to realize that acceptance-level testing is critical to be able to release safely and frequently without a manual testing phase.

A great book that talks about the benefits of integration-level testing and its interaction with traditional Test-Driven Development is Growing Object-Oriented Sofware, Guided by Tests. This book challenged a lot of my traditional assumptions about the level of testing was helpful for a project, both in terms of preventing defects (which I’ve mainly focused on here) and how tests support agile design.