I’ve been leading software teams for about three years now. As a software lead you’re expected to do what it takes to that your team is delivering software that’s high quality at a high velocity. I interpret quality as how well the thing you’ve been building actually works - are there functional bugs, what’s the performance (both real and perceived), and other end-user focused measurables. I interpret velocity as how long it takes for something to go from being an idea to being real - how long does it take you to fix a bug, how long does it take to build a new feature. Quality and velocity are always pulling against one another - we have to move fast, but we can’t move too fast and cut too many corners or else we’ll get swallowed by bugs (customer pain) and legacy code (slowing us down in the future).

While part of my team’s work is continued product support (day-to-day bugs, library upgrades, responding to support escalations), we frequently work on larger features where team members come together to build something together. My team has both frontend and backend-focused team members who are specialists in different areas and contribute to different parts of our codebase. Building a rich UI requires a different professional background than managing persistent state and ensuring that state stays consistent.

Managing the software development lifecycle of a project requires constant prioritization decisions and a high degree of coordination between team members. I fit most of the priority decisions that come up during a software project into a mental framework that I’ll describe in this post. I have a rough four-phase mental model:

- Work to reduce project scope initially - aim to reduce “new” concepts or features

- Make it work end-to-end as quickly as possible

- Harden the feature by making contract-breaking improvements required for full launch

- Release to customers by gradually dropping a feature flag

My background is primarily in web development - we are responsible for an end-to-end user experience (browsers are a pretty mature client platform) and have a deployment that we control and can update at will. I’ve worked on larger projects where my team was just one responsible for overall project delivery, as well as projects where my team owned everything from the UI down to the virtualized infrastructure that our servers ran on. All of my professional experience has been in agile development environments where we work with a product manager to build a feature. The development teams have had processes that rank from high process (following all the Extreme Programming practices) to low process (my current team - kanban without daily standups).

Up-Front Planning and Estimation: Reduce “New” Things

Early on in a product, things are a lot more formless. You’re primarily working with a product manager to define scope - what should you build that will provide customer value? Your job as an engineering lead is to find the smallest project that delivers the most value. Every extra feature that you add into a software project increases the overall project risk. (Unfortunately, software delivery isn’t as simple as one feature means one week - large-sized projects can result in all-or-nothing delivery.)

It’s important here to be honest about delivering value. It’s possible to deliver very small and easy projects that don’t make a big difference to the end user experience. Engineering resources need to be able to say yes to important projects that will transform the overall product - being focused solely on today and the deltas that are possible from the existing code will ensure a static product. Sometimes really big features need to be taken on even if it’s a lot more work and a lot more risk. I like to work backwards from the customer - what does this product feature allow the customer to do that they can’t do now? How would that increase the objectives of the company?

I try to set deadlines that correspond to my rough estimate. Deadlines sharpen people’s thinking and ensure that there is a sense of urgency associated with the overall feature. Sometimes these deadlines are arbitrary - we’ll release a feature when it’s done, but ideally it’s done soon! Being flexible on deadlines is important when they’re arbitrary - ideally the sense of urgency comes from the team and you don’t have to impose it too much as a leader.

I like to give a high level estimation for a project which is usually some delta - e.g., “I think this project will be 3-5 weeks”. This is mainly influenced by how much “new” that needs to be built and how different it is from other projects that the team has done in the past. Ideally projects can use existing infrastructure (code patterns, databases, features). You don’t always get to pick the number of “new things” that you can take on - but trying to eliminate ones that don’t substantially add to your customer delta will result in more predictable software projects. All of the projects I’ve lead that have had to invent a large number of “new things” have been the ones that took the longest and were most at risk.

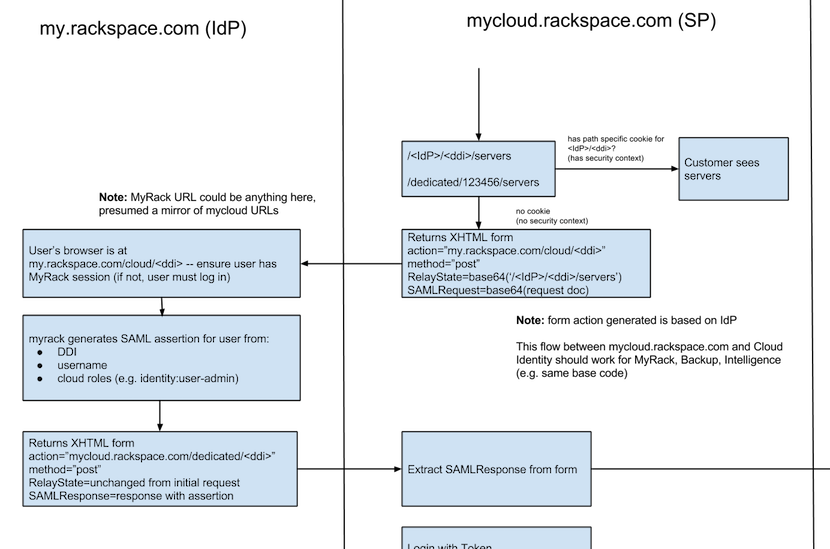

“New Things” - Planning a SAML Login Flow

Converting the Rackspace Cloud Control Panel to be a SAML identity provider stands out as a project with a lot of “new things”. We had to build a new login flow on top of a completely new set of libraries (pySAML), as well as teach the team an entirely new technology. 18 months later, Rackspace has gotten a lot out of that project: it’s enabled product teams across the company to request access credentials from the MyCloud portal through a unified login screen - customers enter their passwords once to mycloud.rackspace.com which gives them credentials to access any other Control Panel that MyCloud recognizes as a SAML service provider. (One of my old team members wrote an article digging into the guts of how it works.) Combined with a shared style library, this has let other teams build out their own Control Panels without needing them to be deployed as part of the main mycloud.rackspace.com portal (this includes the recently out-of-beta Cloud Intelligence).

On digging into the project it was clear to me that we needed to build out a completely new code flow to handle “login to MyCloud as a SAML service provider”. We could re-use our login page, but the backend logic that powered login would have to route the authentication response (containing an authentication token) to a completely different route handler which would then generate and sign the SAML response. (We ended up using a self-signed SSL certificate as we weren’t part of a large PKI system, which complicated things slightly.) I worked hard to make sure that I understood the flow from start to finish, making diagrams in Google Diagrams about each of the intended flows and making sure that the diagrams were comprehensive enough to serve as a “source of truth” in planning meetings. As the project lead I had to make sure that I completely understood every part of the system so I could communicate the requirements clearly to my team and help them with prioritization decisions that might come up in their day-to-day.

The sheer number of new things required made project delivery far from obvious at the start, and we had a number of scares during feature development, including a late night in the office. (I had a great team that just rolled with it - thanks guys!) Something that increased the number of “new things” required to build out a SAML login flow is that our application had a Python backend. Java and .NET have off-the-shelf solutions that make SAML a lot more of a “drop-in” technology. Us using Python and having a completely custom login flow (modified Django login) meant that we had to roll our own solution, increasing the overall project risk.

Making It Work: Building Straight Down

Once a team’s started on a software project, things are still relatively theoretical. We’ve committed to a project, we’ve taken some stories into our team tracking system, and we’re working on it - but we don’t yet know all of the implementation complexities. When dealing with a complicated product built on top of a custom codebase, stories in an agile task tracker are a guess of what parts of the system need to change as driven by product requirements. The actual list of things that need to change may be different than your initially generated stories. It’s important to get away from this theoretical state and validate that the system works as quickly as possible.

I tend to prioritize anything that gets a feature to “work” above anything that gets a feature to “work better”. Of course, that doesn’t mean that getting a feature to work can skip on important things like unit testing, following good coding practices, or the overall health and stability of the system. But if there’s a “quick and dirty” way to implement a feature that might not be perfectly factored, might not scale to our full customer base, might need a few more database migrations until the persistence layer is what we want, or uses an outdated coding pattern that just happened to be easier at the time - these are all things that are okay to sacrifice on the altar of making it work. Of course, everything here should be behind a feature flag so that customers don’t have a chance to see your quick and dirty code!

Building Straight Down … and Hitting a Wall

Another project that I worked on at Rackspace was the Service Level Upgrade project. As background, Rackspace sells hosted services with their value-add “Fanatical Support” - they aim to attract support-minded customers who want to solve problems with a phone call rather than getting their own hands dirty. In order to really support this kind of customer, it’s important that their public cloud infrastructure comes from a set of base images that has special software installed on it that hooks into the Rackspace support system. At the time, Rackspace also provided an unmanaged public cloud option - but the company really wanted to upsell you to go with the managed public cloud option - better service at a higher monthly rate. The first version of the Service Level Upgrade project involved building new UI screens for customers to request an upgrade and see the status of all their unmanaged servers as they were converted into managed servers (with the special software installed on it). The actual upgrade would be done by an automation engine that would connect to the servers and run a software install on eacah one, after which it would become a managed server, and we would show in the UI that it had been successfully upgraded.

My team was one of a few involved with this project and we had a really hard time getting to the point where the whole thing worked - it required integrating with a new API, parsing an ATOM feed, and then displaying that ATOM feed on the page as HTML/CSS and handling any state transitions from the API. The project as initially scoped out was a failure - we never delivered this to customers and all the development time involved was wasted. One of the main signs that this project was at risk is that the engineering team had a hard time getting the entire system talking end to end. Getting the frontend (Control Panel written in Java, deployed on Tomcat and running on Linux) and the backend (a service bus powered by older Microsoft technology) communicating proved to be very challenging. Additionally, the upgrade process wasn’t able to be validated in the staging environment because the automation engine that would actually do the server upgrade process wasn’t able to connect to our staging environment - at best, we could validate that a request was sent and received with the appropriate data. We’d have to trust that the actual upgrade process (what the customer wanted) would actually work when it came time for the automation engine to connect to the box and upgrade the software.

Eventually major concerns around the likelihood of automated success (very low due to the heterogenity of customer installs) killed the project. About a year after the project’s failure, we implemented Service Level Upgrade in the next generation Control Panel (JavaScript and Python) as a modal that generated a support ticket that would be later processed by a support team member. This wasn’t as good a user experience as the original project would have been (you didn’t get to see the upgrade process in action, you would only see updates to the ticket that were manually added by support), but our implementation only required that we validate a support ticket was created in the appropriate queue. Much easier, and ultimately more successful.

Hardening the Feature

Once a feature works in a quick and dirty fashion, it’s time to make sure that the feature meets a minimum quality bar for release. This means getting the code in a good place and working through both manual testing (primarily exploratory) and automated testing (primarily end-to-end happy path testing). In this phase I consider it completely okay to change database schemas, break API contracts, and completely change the UI. We got the feature working in a quick and dirty way, so we know the feature is possible. In this phase, it’s time to build the feature so that it works every time at a quality level we’re happy with.

For manual testing I try to run through all of the different user scenarios and be as thorough as I possibly can be, but many eyes are the best for exposing issues. At Tilt we release features early on to our employees and college ambassadors to hammer at a feature through a friendly set of eyes. Issues discovered by exploratory testing get added to an agile board and we determine whether or not they are blockers for overall release of the feature.

For automated testing I have primarily used Selenium. The main reason to introduce end-to-end tests at this phase is to catch regressions that might unintentionally pop up. Having automated tests in place early on in a project can be a real lifesafer because it removes a lot of mindless manual testing that you might otherwise do, and to know whether or not a feature is working you can check the status of a Jenkins job.

Like the initial implementation, hardening against a full environment like production. Customers never see this phase of development because they never see any of these features - they are hidden behind a feature flag. It’s important to be constantly integrating your branches and fixes into a mainline - and deploying these changes to production frequently. This ensures that many in-development features don’t conflict with each other because the development team is constantly merging the mainline into their own in-development features, all of which run on a continuous integration system.

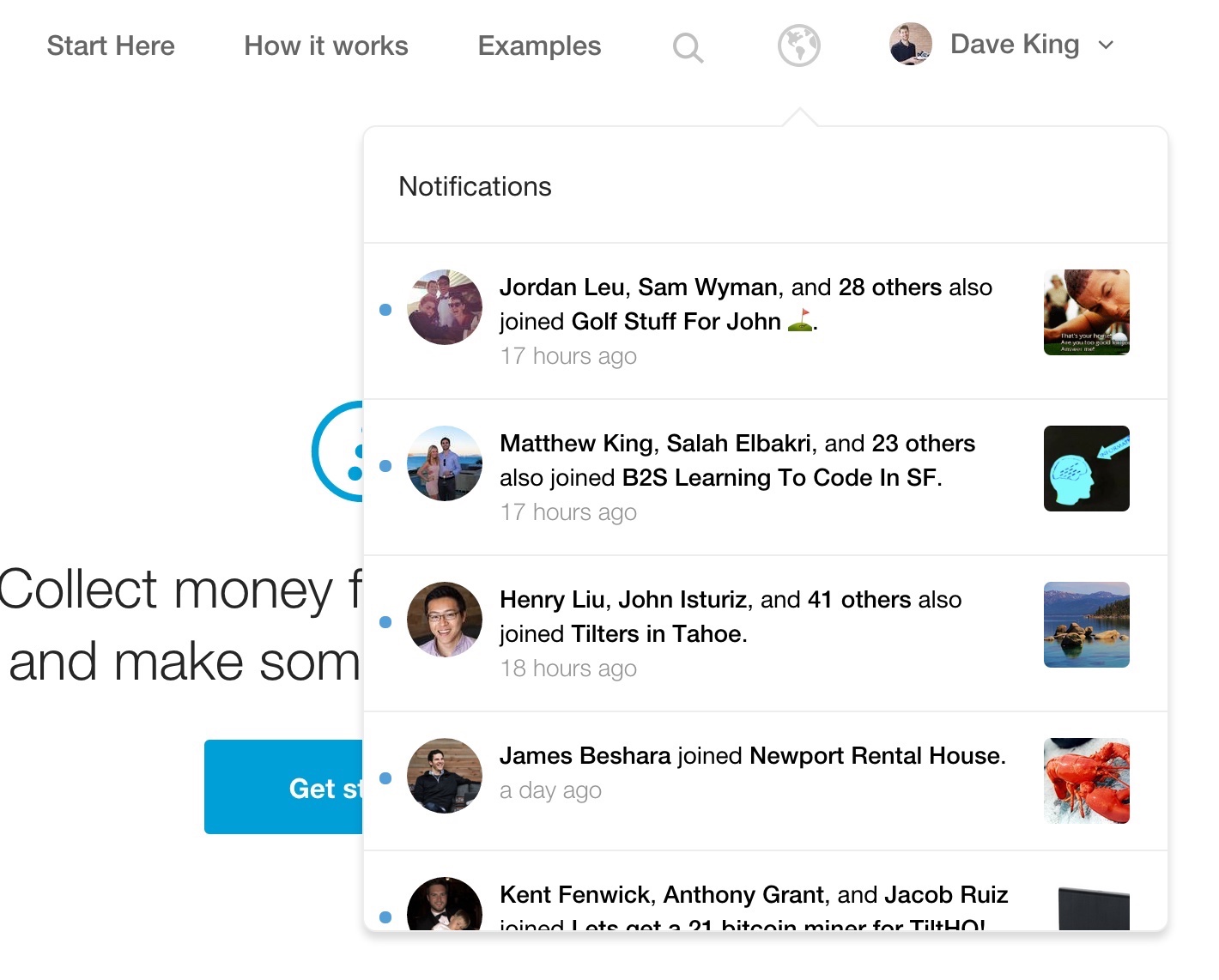

Building Out The Tilt Notification Center

A feature I recently ran through a hardening phase on was Tilt’s notification center, released last April. The Tilt notification center allows tilters (users of the Tilt platform) to see information about which crowdfunding campaigns their friends have joined, whether or not someone responded to their comment, whether or not campaigns that they’ve contributed to were successful - think Facebook’s notification center, but for group payments. This feature was built by several teams working in parallel - a web team (my team, responsible for the UI widget), an iOS team (responsible for the same UI widget as part of the mobile app), and a backend team (responsible for the data returned from an API).

We built the first version of this code behind a feature flag, getting one notification type working, and then slowly added to the feature. We built the desktop version first, and only after this was in a good place did we work to make sure that mobile web worked as well. During this time we were also doing manual testing in parallel - because we had the new feature behind a flag, we could test in production with our actual mobile devices (rather than simulators or faked user agents).

We had to work through a number of issues that came up when integrating the backend (owned by another team) and the frontend - these included ensuring that the data came back in the expected format as well as that the right user actions on the platform generated the right events that eventually became notifications in a user’s dropdown.

During this process we added very aggressive error handling to detect frontend and backend integration problems - on every JavaScript exception that resulted from parsing the notification data into HTML, we wrote an error into Rollbar. This quickly surfaced bugs that would come up in the course of testing. We also built basic Selenium tests that verified certain actions (contributing to a tilt) would generate the expected items in a user’s notification center. These tests let us verify that everything kept working end-to-end as we pushed new features.

Releasing the Feature

Once we’ve worked through all the blocking issues and we’re convinced that we’ll be releasing something that’s a value add to our users, we’ll roll out the feature by dropping the feature flag. At Tilt we’ll use Optimizely to gradually roll out new features to more and more of our customer base. This gives us a convenient way to instantly turn off a feature if a show-stopping bug is identified without requiring a code push.

I’ve also built server-side feature flags: when one of my past teams was migrating our database from MySQL to Cassandra, we were able to scale up and down which users wrote data into Cassandra and which users read data from Cassandra independently. This allowed us to understand the database’s failure scenarios without impacting the overall customer experience.

Ideally releases are boring, and releasing a feature requires very little code change on your part the day of. Things you’re releasing to customers should be bullet-proof and you shouldn’t hear any surprises. I like to release things early in the day: the team is at its highest energy to respond to any issues that come up, and you don’t need to ask people to work into their nights. This is made possible through having a zero-downtime deploy process - a necessity for a high performing software team.

Conclusion

I’ve worked on a number of large-scale software projects up and down the stack and they’re all pretty different. My favorite projects have been the ones where my team was totally responsible for overall success: we own the code that shapes the visual user experience, we own the API code that powers the user experience, and we own (or at least have ability to change) the infrastructure that ensures that backend servers can always respond to client requests. Looking back on my development history, the projects which have been the most frustrating are when two software teams with differing quality standards need to integrate. Before taking on a cross-team software project, I’d recommend sitting down to manage expectations around how work will be done and what the cross-team deliverables will look like.

In describing these past projects I take CI/CD as a given - integrating in-development code into a deployed production system frequently is critical to avoiding customer surprises. Feature flags and phased rollouts mean that you shouldn’t ever need to stay up until 3am doing website deploys. I wish everyone a good night’s sleep.