I was once debugging a deployment issue where one server wouldn’t send outgoing email, even though it was running the same version of our application software as other machines that were functioning just fine. After a while I traced it down to the fact that four years ago a developer had stuck an extra mail JAR file into the Tomcat lib/ directory. This incident showed me that every server performing a function should be exactly the same as every other server performing that function.

Configuration Management with Chef

Configuration management allows system adminstrators to ensure that systems running in production all look and behave the same. The technology used by my team is Chef, a system where you specify system configuration in a Ruby DSL. (I have also set up the Chef configuration required to set up a server hosting this blog.) As an example, here’s the Chef resource that I use to ensure that Apache is installed on the servers hosting my blog:

package "apache2" do

action :install

end

While that’s a little simple, here’s the Chef configuration for my blog’s deploy process, which involves cloning a repository from Github, building it with Jekyll, and dumping the files into /var/www:

git "/tmp/davehking.com" do

repository "git://github.com/tildedave/davehking.com.git"

reference "master"

action :sync

end

script "Generate site and install in /var/www" do

interpreter "bash"

cwd "/tmp/davehking.com"

code <<-EOH

compass compile --force

jekyll --no-server --no-auto /var/www/

EOH

end

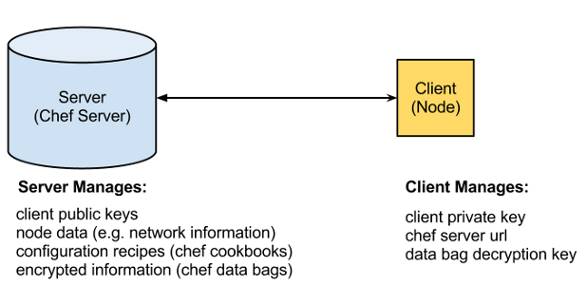

The default OpsCode offering is Chef Server, a server that stores configuration management files (“cookbooks”), information about servers that can connect to it (“nodes”), and stored data requires to provision a sever successfully (“data bags”). Setting up a new client to a Chef Server requires creating a public/private key pair and then running chef-client, which pulls down recipes from the server and executes them on the client.

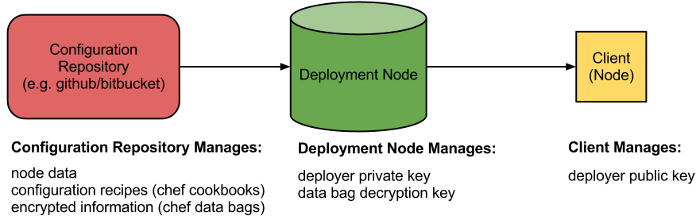

LittleChef is a library for running Chef configuration management on infrastructure without requiring a centralized server. It’s built on top of Fabric, a Python library for automating system adminstration tasks across multiple servers. It uses rsync to push cookbooks from a trusted deployment node to the client, and then runs chef-solo to execute these cookbooks on a client from the filesystem.

Trust: Chef Server vs LittleChef

The main distinction that I see in between these two technologies is how in Chef Server, the client is assumed good (private key on client, public key on server), while with push models such as LittleChef, the connecting user is assumed good (private key on user, public key on client).

In Chef Server, you maintain a long-running trust relationship between client and server, and this trust relationship is a special protocol specific to chef-client. The client maintains its own private key as well as a decryption key required to understand secret data that’s stored on the Chef Server.

Using a push model such as LittleChef, you replace this trust relationship with the trust relationship required for ssh access: users that have sudo access now can deploy. Data (cookbooks, node information, and data) is stored in a source control repository, possibly hosted on some external SaaS site such as Github or Bitbucket). Secrets such as the private key required for connection and the decryption key required for the secret data live on the deployment machine or machines.

While the deployment node might be your developer machine, I wouldn’t recommend this as your only solution as your team grows. LittleChef enables a better workflow for testing recipes on remote nodes; push then commit rather than a upload possibly bad configuration to the server. Production deploys should happen from a controlled box with an automated process, using automation tools such as Jenkins, Deployinator, or Dreadnot (what my team uses).

The data bag decryption key no longer being on the client is bit of a red herring: the data bag decryption key is copied to the client during deploys and removed afterwards. Besides, if you are writing formerly encrypted data unencrypted into your configuration files the client still has access to all the same secret information.

Why Switch?

My team recently transitioned from using Chef Server to using LittleChef. Both have their advantages, but there are a few reasons why LittleChef made more sense for my team.

Small Number of Nodes

My team currently maintains less than 100 servers across all of our environments (including our development and logging infrastructure). This is not a lot and our architecture is relatively basic, with only a few different types of servers: our stack is Apache, MySQL, Django for web application development, Twisted for web service calls. This low level of complexity allows developers to work closely with the deployment environment and understand every aspect of the application as it goes from development to production.

This small number of nodes lets us avoid maintaining a chef server and troubleshooting issues with services like solr, couchdb, rabbitmq, MySQL, or PostgreSQL (depending on which version of Chef Server you’re running). The easiest server to maintain is the one that you’re not running!

Cloud Deployment

Our infrastructure is hosted in the Rackspace Public Cloud, which gives us the flexibility to spin up new nodes to handle traffic as need arises, as opposed to needing to plan for our capacity 3-4 months ahead. This makes the trust relationship between client and server less important as clients can be created and disposed as necessary. In this situation, the Chef client configuration (requiring setting up a private key, a named client, and registering it with the server) is a mostly-unnecessary barrier to creating a new server.

All Servers Support One and Only One Product

We don’t have any servers in our infrastructure that support multiple applications and we deploy daily to production to all of our environments. This allows us to centralize control of our configuration management in one place (a github repository) and we don’t need to worry about affecting uptime of other products as we make changes to our infrastructure.

Things We Ran Into While Switching

In making the switch between the two, we ran into a few issues. None of these were fundamental problems but these may be useful if you’re making the same change on your team.

Data in Chef Server Not in Git Repository

We use a git repostiry to keep track of our chef data, which is then uploaded to Chef Server on commit. However, certain nodes and data bags were not stored in this git repository but instead only existed in the Chef Server. This required discovering which data was missing and then adding it manually, as well as auditing all nodes registered with the chef server to determine whether their data should also be migrated to the LittleChef repository.

Knife Solo for Creating Encrypted Data Bags

The Knife Solo library duplicates many functions that usually require a chef server. The Knife Solo Data Bag library adds encrypted data bag management to Chef Solo, allowing the creation of data bags that contain secret passwords.

Attributes in Roles, Not Environment Files

My team set certain attributes in environment files, which is not currently supported in Chef Solo (though a patch is being worked on). To fix this, we moved these attributes into roles and added this role to each node in the environment.

While this was a bit of a hack, it’s let us clean up some of our configurations. For example, feature flags that were previously set to identical values in both our production and preproduction environment files now share the same role to ensure that they keep the same behavior.

Conclusion

If you’re deploying to the Rackspace Cloud, I’ve put together littlechef-rackspace, a library for creating a new server, deploying Chef with LittleChef, and provisioning it with a specified runlist. It’s still pretty basic (only supports server creation) but I’m going to be adding more features to it soon.